Extract from the unpublished memoirs of John Neill Harris OBE, MC and Bar, BSc

b 2 June 1914 d 25 October 2009

VI APPROACHING WAR

War was meantime fast approaching. In the spring of 1939 the War minister Leslie Hore-Belisha of yellow beacon fame, doubled the territorial army. Reggie Ferguson and I discussed endlessly in our joint office whether or not we should join up.

I lived in digs in Glenloch Road, Hampstead by Belsize Park tube station (with a group of Jewish refugees from Germany: half-board and Sunday lunch £2 per week) and Reggie in West London. He rang a Territorial regiment in Kensington and asked about recruiting days. The answer was Friday evening and Reggie said that was the one day we could not manage. I can still hear the recruiting sergeant’s response, did we think the army was there to suit us or vice versa etc. etc.!? So that was that – pity, because that was a medium gun regiment well back from hand to hand infantry stuff which we did not relish!!

Then a friend of Winch’s, Jack Hawkins of the Autocar, happened to call into our office. He said he had just joined an armoured car regiment whose HQ was near Lord’s Cricket Ground and named the 4th County of London Yeomanry (“Sharpshooters”). That suited me fine and Reggie joined the London Scottish. I went along with Jack in April 1939 to volunteer – as a trooper (private) quite forgetting that I had passed Certificate A in the school OTC which entitled me to be trained as an officer on the outbreak of war. So I had 18 months in the ranks – no bad thing.

Winch had also been involved in our military discussions. His father had been killed in 1918 and he (like me !) was a member of the pacifist Peace Pledge Union. Spark decided not to join up then and went on the outbreak of war to help in a Governmental scheme to encourage flax growing in South East England. In 1940 the Germans dropped a bomb on a block of flats in South East London killing Spark’s mother, sister and aunt. He volunteered for Bomber Command, won a D.F.C, was shot down and was two years a P.O.W. He died in 1999, having worked happily running the Shell experimental farm in Kent.

One Friday evening in late August 1939 as I was putting to bed the Irish edition pages of the Farmer and Stockbreeder at Cornwall Press there came a phone message for me to report forthwith to 4CLY which had been mobilised. The Farmer and Stockbreeder management were very supportive: we all had an unwritten promise of employment at war’s end and received a very small financial grant throughout the war (I think about £1 weekly for me!). There were enough older men to keep the Farmer and Stockbreeder going until more women and men unfit for active service were recruited.

Our regiment had trained every week at Lords and in July 1939 went to camp at Micheldever, Hampshire, in fields which I now pass every time going fishing on the Test. Then in August having reported to the regimental offices that Friday evening we were then sent home to be at 12 hours notice. We were allocated army numbers, mine 7894877. A few armoured cars arrived. There was nowhere to park them and it was decided to put them in an underground car park near Chalk Farm tube station. Down they went via a lift. It was discovered next morning that the lift counterweights were not heavy enough to bring the cars up again. The nearest adequate weights had to be fetched from York!

Life was chaotic. We had battledress but no overcoats so we were paid 1s 6d (7p) a week to wear civilian ones! We had no arms. War had been officially declared on Sunday 3 September 1939: we listened to Chamberlain’s broadcast wondering what would come next. In fact it was a false air raid warning. The next six months were to constitute the ‘Phoney War’ when neither side took much action.

Late in September 1939 we went off to Woolacombe, a nice Devon seaside resort. I slept in the best room in the Bay Hotel, with half a dozen others. We still had no fighting vehicles, so did only dull routine training – and enjoyed ourselves during a wonderfully sunny autumn. After a month or so I was selected to go on an anti-gas training course at Winterbourne Gunner in Hampshire. How and why I was chosen I have no idea! But it meant I had to be uplifted in rank to corporal. The course taught us to become instructors in how to deal with a gas attack, what precautions to take and so on. Most other NCO’s on the course were regulars : I remember amazement at their lighting a cigarette on waking, then entering a violent coughing fit! We were never to encounter gas in the fighting.

At the end of the course there was an exam. As I said above I had always at school and at Wye found I could absorb and retain for a few weeks at lot of information, and had had a good grounding in English. So exams had no terror for me. I returned to the regiment to be told that I had been a credit to the 4CLY and had received a very good report. I would be recommended to be in charge of the anti-gas training centre to produce enough instructors for the whole regiment (600 all ranks), planned for the near future.

Then health, rather ill-health, intervened. A few days before I was due to go to my home in Trysull, Staffs on Christmas leave I developed severe cold symptoms, lost my voice and knew I had a temperature. I struggled to Wolverhampton by train where I had to get a porter to ring to tell father that I was at the station. I went straight to bed. Dr. Goldie came that night or the next morning and diagnosed pneumonia – but quickly added that was then much less serious than previously thanks to a new drug called M&B (May & Baker) – the first antibiotic. I had horrible memories of pneumonia, on three or four occasions, including 1917 and at the end of the Easter Term of 1929 when I was in the sanatorium at Mill Hill as the holidays began.

By the time I was fit to return (after 3-4 snowy weeks), 4CLY had moved to Worksop in Notts. I arrived there in a bitterly cold early February, and was shortly detailed to head the regimental anti-gas training centre at a requisitioned house called Netherfield on the outskirts of the town. From Worksop I was to go on marriage leave in May. I will elaborate shortly on that critical event in my life.

I had one narrow squeak at Worksop. Every Sunday morning one set of students left the Gas School and another arrived, lorries bringing and removing heavy kit. I came out of Netherfield House to find one such lorry departing for the town a mile away where we fed. I jumped aboard alongside the driver. He dropped me, then proceeded to his own squadron HQ and went off to lunch. The Orderly Officer passing by that HQ had a look at the said lorry and saw in the back a dozen or so rifles. Now, in the British Army a soldier is required to guard his rifle with his life. Who was responsible, wondered the OO, for this breach of discipline that left a heap of rifles there for the taking by any terrorist? Alarm bells rang!

When I arrived back at Netherfield, blissfully ignorant of all this kerfuffle, I was met by the said OO and told I was under arrest. He had discovered he said that I had “assumed command” of the lorry in question, being a corporal and the driver a trooper. I was hauled before my squadron leader and advised of the seriousness of this ghastly lapse of duty, a matter which might result in court martial and so on. I was saved by an officer of my squadron, one Sandy Scratchley. Sandy was a famous hurdle race amateur jockey, the best of his time, a man of great common sense who saw such innocent derelictions of duty in their proper perspective. He intervened on my behalf, said I was a useful NCO and so on. The Squadron Leader took heed and the matter was dropped. The driver is to this day on the Committee of Sharpshooters Old Comrades Association and we have exchanged recollections of these events!

In retrospect this incident seems trivial, but has to be seen against a chaotic time when Hitler’s armies were expected to invade, and fifth columnists to lurk round every street corner looking for arms in due course to use against their own countrymen. By now the German armies were streaming across Europe and in June was to come the Dunkirk rescue.

VII A WARTIME MARRIAGE

The long expected end to the Phoney War which had lasted since September 1939 finally came on Friday morning 10 May 1940. I had a 72 hour pass to proceed (as the army verb always had it!) that very afternoon on marriage leave. All leave for all services was cancelled on the Friday morning, but a friendly adjutant (Gerald Walker of Johnny Walker whisky, alas later k.i.a.) came to the rescue of Corporal Harris and issued a pass reading ‘proceeding on training course’. Our best man, brother Mike, was held up in London on short notice to go with his battery to France. Other guests had to cancel, for the country was in chaos.

Nevertheless our marriage by Vicar Bennett in All Saints, Trysull, went off well.

At the end of our brief honeymoon I returned to my regiment which by then was in a tented camp in Clumber Park in the Nottinghamshire Dukeries with some elements on the East Anglian coast expecting German invasion, armed only with rifles and a few rounds of ammunition. I dread to think what would have happened if the Germans had come!

VIII THE GUARDS AND SANDHURST

A fortnight before Dunkirk I had been sent to spend two weeks with four other sergeants (a rank I had lately attained) for training in drill at the Chelsea Guards Barracks. What that had to do with warfare in armoured cars or tanks I know not. But we had as second-in-command of 4CLY a Guardsman relative of Anthony Eden!

After 5 or 6 days soldiers came back from Dunkirk in their thousands, our course was cancelled and back we went to 4CLY. We sergeants were not sorry to be returned to our regiment. The discipline at the Guards depot was ferocious, any soldier returning from Dunkirk without his rifle was, for instance, automatically put on a charge. Our first afternoon we were detailed for P.T. and turned out in our motley gear of coloured rugby shirts etc. As we crossed the parade ground there was a great roar from the orderly sergeant : who are those horrible men, arrest them! We were within minutes in the QM stores issued with army vests, regulation soccer style shorts and worst of all brown gym shoes.

The regiment was now under canvas in a splendid park outside Kettering. It was equipped with cruiser tanks and moving fast toward readiness for action. One day in July 1940 my squadron leader, George Kidston, a regular cavalryman of some renown who was in due course to command the Sharpshooters, asked me whether I would like to be recommended for the Royal Armoured Corps Officer Training Unit at Sandhurst, Camberley in Surrey. So there I went in August. Kidston’s decision to let me go may have been influenced by the fact that I was something of an oddity having missed troop training with the tanks because of Netherfield, the Guards course etc.

Off I went to Sandhurst in August. There were about 20 of us in No 25 Troop, at least half straight from civilian life, others like me risen from the ranks. As a sergeant from a very fine regiment I knew more about the army than most of them, or thought so, and was a fairly easy going cadet.

We cadets were assigned certain senior other ranks’ jobs for a week at a time and I gained some notoriety one Saturday night when Guard Commander on the Yorktown Gate into Camberley High St.. In the middle of the night two rather drunk regular staff sergeants who trained us cadets came bellowing into the Guard tent using colourful language to the effect that the sentry on duty was an idle so-and-so, typical of all the useless cadets. One of them announced that he would demonstrate his opinions, and promptly relieved himself in the entrance to ‘my’ guardroom. Aware of the military procedure in such matters I shouted “Turn Out the Guard” and told them to put the staff sergeant under close arrest in the back of the guardroom and take off his boots. I was later told that no cadet had ever done such a thing.

The other staff sergeant had meanwhile beat it to the Main Building and the Orderly Officer, a peacetime Beaverbrook man named Mike Wardell, came to our guardroom. He ordered that the prisoner be temporarily released ‘without prejudice’. Next morning I had to fill in the Official Guard Report which required a list of prisoners. I entered my released prisoner’s name.

All hell let loose when one Brand, the Regimental Sergeant Major, a figure of great significance at Sandhurst, heard what had happened to one of ‘his’ staff sergeants. A major enquiry took place, in the course of which the Adjutant who virtually ran the RAC wing sent for me. He took my side but said he simply could not do so publicly – though this affair was to have a considerable influence on my military career.

Our course, which included a visit to Lulworth to shoot from tanks, ended in mid-December with the usual passing out exams. I had been a figure of modest stature so far, but the exams were just my cup of tea and I was awarded the one ‘A’ in the troop.

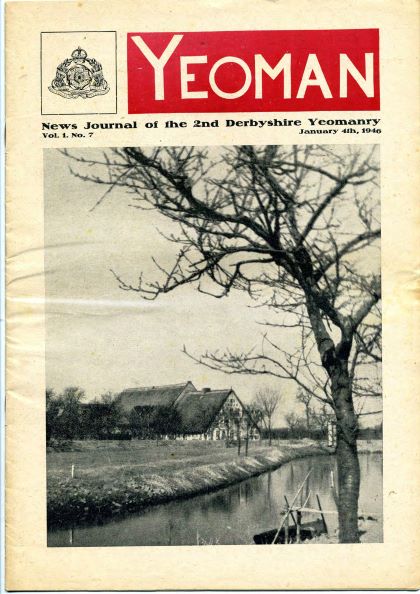

I had already decided to join the Royal Tank Regiment if I passed out successfully, mainly because this modern set-up, dating only from the end of the First World War, comprised ordinary blokes without great cavalry traditions and in which officers were expected to be able to live on their pay – very unlike, for example, 4CLY. The adjutant sent for me, recalled the Yorktown Gate incident, proclaimed his congratulations on the ‘A’ and said that of course I must go to a regular cavalry regiment. He would fix things for me. Would I like to return to the CLY or this or that famous regiment? I declined, to his astonishment, but he accepted what I said about the money side. I should go away and return next day by which time he would have thought the matter through. Next day he said he had spoken to a relative of his in the 2nd Derbyshire Yeomanry. They were short of officers, had no high faluting messing charges, would love to have me, and so on. I accepted.

IX PREPARING FOR COMBAT

Mid January 1941 saw me at Kirby Malzeard outside Ripon, troop leader of 4 Tp, B Squadron, 2 Derby Yeo, the Squadron commanded by the one and only Tom Pearson, who looked after me as though I were his only son. Tom was a farmer from near Ashbourne, a real old fashioned Yeoman, brimful of common sense who ran his squadron in a fatherly fashion.

We looked for digs around Kirby Malzeard. They were very scarce and the only possibility turned out to be a lonely farm deep in the snow covered countryside of an exceptionally severe winter, with very little in the way of modern conveniences.

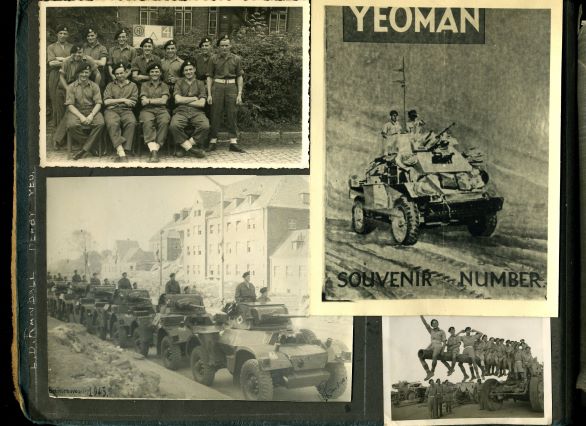

We trained hard in the bitter cold. Several members of my troop turn up to this day 60 years later at 2 Derby Yeo Reunions in Long Eaton, notably my then troop sergeant, Chalky White, later Squadron Sgt. Major of B Sqn. Also Peter Fountaine who died lately. He drove my light armoured car which together with Pat Macnaghten’s armoured car and a half-track vehicle comprised our Squadron HQ in Europe.

We were equipped in 1941 with Guy armoured cars, made in Wolverhampton, most unreliable vehicles typical of the armoured equipment which the British had to accept until America came into the war. I remember one amusing moment when the CO held a regimental inspection of the armoured cars. As he passed one car the air was rent by a loud squawk. If there was one sound our Colonel recognised it was the call of a cock pheasant – and such was indeed revealed, secreted in a comfy corner of the ammunition rack!! Quite a row ensued.

In March 1941, with great relief we left the snow and ice of Yorkshire for Gloucestershire – the small town of Wotton-under-edge. I was transferred from B Sqn. into Regimental Headquarters to help teach recruits from the North Staffs regiment to drive.

In midsummer 1941 we moved to Surrey in and around Charlwood, where regimental HQ was and I became assistant adjutant to Tom Killick. In particular, I remember, the War Office decreed that an armoured car regiment was now to have four not three squadrons. The C.O., the wily regular James Browne asked Tom and me how we should set about this, assuming each existing squadron would contribute one quarter of its personnel with a stated complement of NCO’s, skilled tradesmen and so on. Just tell them to do that, we said. “In which case we shall get their least desirable quarter and lose the essential balance of squadrons of equal skills,” responded James. The answer is, he explained “to tell each squadron to divide their men into 4 equal segments and I shall draw one quarter from each by lot. They will balance the quarters very carefully.” he went on. They did.

When D Squadron, the fourth, was eventually formed I was promoted captain to be its second-in command. In December we were warned for overseas service and everyone went on embarkation leave. Then in typical military style the overseas posting was cancelled. We had moved meanwhile a short distance to Maresfield Camp near Ashdown Forest and there spent the early months of 1942. The CO decided Tom Pearson was too old, he was certainly over 40, to command a fighting squadron so he was moved to the administrative HQ squadron, Tom Killick took over B and I became Adjutant (rank remaining capt.). General Montgomery came in March or April to inspect us, following which we were told that James Browne would relinquish command and by a most unhappy coincidence our second-in-command, the much respected John Cairns, was claimed at the same time by his own RTR regiment to command them. He was to be killed in the Desert.

New OC and 2nd I/C would arrive shortly we were told by 8th Armoured Division of which we were part. I had quite a load to carry meanwhile, especially as departure overseas was now expected early May.

During April Lt Col Viscount Allenby, regular 11th Hussar cavalryman and nephew of the great WW1 General Allenby and successor to the title arrived to command us, followed by another 11th Hussar Major Peter Wiggin as second-in-command. We departed in due course from Crowborough station, going through the middle of London on the Metropolitan line and on to the Clyde and sailed from there on 7 May 1942 in convoy, half the regiment on the ‘Strathnaver’, half on ‘Monarch of Bermuda’. I was on the first named, in which my father had travelled to India in peacetime.

X THE WESTERN DESERT

We called at Freetown, then Cape Town for four days of wonderful South African hospitality. The voyage was uneventful though being such a bad sailor I felt pretty miserable. There must have been 1500 or so on board, including a military hospital whose nurses cheered things up a bit. I remember so well going up on deck at night looking back on the great convoy of troopships, guarded by the majestic destroyers. We reached Port Suez on 5 July, went by rail in cattle trucks to the Delta to train furiously in desert warfare, most particularly how to find your way about the desert by compass, sun compass and the stars.

The military situation was desperate. The 8th Army had stopped the Germans on the Alamein line (the battle now called first Alamein), the last defensive position before Alexandria and the open road to Middle Eastern oil and the underbelly of Russia. The next German offensive was awaited. Within a month we were in the line, briefed for a typical role for an armoured car reconnaissance regiment like 2 Derby Yeo, when in a defensive battle. That is to monitor the enemy’s movements to give vital warning to heavy artillery, dug in tanks, anti-tank guns and so on. Lightly armoured cars should not get involved in fighting unless things go wrong. Our armoured cars were in position watching the minefield gaps as the Germans advanced on the night of 30/31 August 1942.

For once the Germans made mistakes in this the battle of Alam Halfa (now called second Alamein). Their tanks drove straight into well prepared British defences, lost heavily in tanks and men and after a week’s furious battles withdrew without gaining any ground. The Alamein line was unbreached; the Germans had lost their last chance to win the Desert War. Our troops on the minefield gaps had done well in an unpleasant role often heavily shelled but unable to take avoiding action. We earned the praise which came from higher command.

As adjutant I operated in a four man armoured car cheek by jowl with Jaff Allenby. We directed affairs but of course were not expected normally to have direct contact with the enemy. The 8th Army allowed all manner of dress and most officers wore corduroy trousers and suede desert boots made by one Lyras in Cairo. In the chase after the Alamein victory our Regimental HQ did encounter some Italian lorries and Allenby roared for the gunner to traverse on to the target. Alas to the CO’s furious dismay my trousers jammed the turret traversing gear solid and immovable!

Alam Halfa was General Montgomery’s first battle. He had the advantage of large numbers of American Sherman tanks able to match the Germans, in sharp contrast with his predecessors (in particular Auchinlech) whose tanks were so hopelessly out-gunned. Monty’s stock rose rapidly, as did the 8th Army’s morale. We still had to drive the Germans back, but believed we could do just that when the time came. Moreover, Monty’s reputation gave him the status to resist demands to join the next battle before he judged the moment right.

That moment came on the night of 23 October 1942, the opening of the Battle of El Alamein, among the crucial conflicts of the Second World War. A furious infantry battle lasted more than a week while armoured car regiments and tanks waited for a hole to be punched in the German-Italian line. It came in the early days of November, and the chase was on. Thousands of the enemy surrendered, streaming on foot across the desert, but every now and again they stood their ground, and amazingly on 5 November there was a great rain storm after which vehicles sank in the sand up to their axles.

We lost cars through breakdowns, the Humbers not much better than the Guys they replaced, through enemy guns which could easily pierce our thin armour and above all by cars blown up on mines. The Humbers had exceptional ground clearance which made them a better target for enemy guns, but conversely meant all four wheels could be blown off by mines without human casualties.

We started with 60 armoured cars (brought by slow convoy from the UK). By the time we approached Tobruk we had under a score of ‘runners’ and were ordered to pull out of the chase, to refit. We assembled not far from Tobruk on a patch of sand by the sea, in which we swam, even on Christmas Day, expecting new cars by the day.

New cars did arrive but the powers that be had decided that only two of the five armoured car regiments could be re-equipped and that preference would go to the regular regiments. We did scratch together a dozen or so cars which went on to Tunis doing escort duty for Montgomery and his c-in-c General Alexander. The rest of us waited and waited until early March when we were moved back to Alexandria – well illustrating the fact that war is long periods of boredom interspersed with brief bouts of exciting action! We saw the Bedouin drill barley in the coastal strip of Desert sand in November and reap the foot high harvest in February.

So our desert war was over. In retrospect we all agreed that if one had to do battle the Western Desert was an appropriate place – no civilians to speak of, no towns, no livestock and so on. It was very hot by day, but in November the nights were chilly and one slept well under the stars (or under your armoured car when in action). Each vehicle crew fed itself though on very basic rations. We managed well on a gallon of water a day for all purposes. On supplying itself the British army was very good. We were never hungry nor short of fuel. Mail came up regularly. There was leave to Alexandria (and its awful bedbugs!) when things were quiet.

Towards the end of the post-Alamein chase Lord Allenby decided that the commander of B Sqn., Tom Killick, should be replaced – by his adjutant. Surprisingly, Killick elected to stay on as my second-in-command, reversing our previous role of adjutant and assistant adjutant. Thus from November 1942 I was a Major.

I shall never forget my often tempestuous eight months as adjutant to Jaff Allenby. He was a very forceful character bearing a name still of great renown in the Middle East. He held in fierce contempt those who spent their war – the more senior the better – propping up the bar of Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo consuming “Suffering Bastards” (gin, fresh lime etc). Jaff Allenby stood down in April 1943.

Another cavalry colonel followed, Rodney Palmer of the biscuit dynasty but come the invasion of Europe he was evacuated wounded. Then Walter Serocold (family closely connected with Watneys) of the Reconnaissance Corps took over to the end of the war.

Two final desert memories. Standing-to one morning at first light a lot of our tanks passed close to us and Allenby asked me if I noticed anything odd about them. I had not realised that these “tanks” were silent, no roar of tracks. They were dummies made of canvas on lorry chassis, part of a whole division deceiving the enemy. And lastly when the opposing armies were a few hundred yards apart before Alamein, the haunting strains of Lili Marlene coming across from the German lines in the cool of the evening – unforgettable! The best tune of the war.

XI VIA ISRAEL TO NORMANDY

Back at Alexandria in March we were told to prepare to become a ‘Brick’ – a formation which takes charge of and protects a landing on foreign soil, in our case intended to be the islands of Kos or Leros. So we trained for this combined operation for six months in Israel, on the coast between Haifa and Tel Aviv, in sweltering weather. We were expected to land by scrambling down nets on the side of ships, for which I was not designed.

In November, mercifully, we were ordered to hand over our Brick role to another formation and proceed back to Suez for transport to England to get ready for D-Day. The Mediterranean was by now clear. We arrived in Liverpool on 6 January 1944, welcomed by a quayside band playing “There’ll always be an England”, then on by train to Hartwell House near Aylesbury and home leave.

I returned to train my squadron in a new role. We were to become the reconnaissance regiment to an infantry division, the 51st Highland, whereas in the desert we had a much more mobile role in 7th Armoured Division (the ‘Desert Rats’) and similar formations. Each squadron would have three armoured car troops, three troops of tracked carriers and one assault troop of about 20 infantry men.

On 6 June 1944 the D-Day landing took place, as the world knows. My squadron travelled to Tilbury on the morning of D Day, waited two days there, before embarking and landing near Colombiers-sur-Seulles on the evening of D+4. C Sqn. had landed on D+1.

We drove ashore from our “Landing Ship Tanks” in fairly shallow water (ages had been spent in waterproofing the vehicles, exhausts carried up in the air) without losing any vehicles and without opposition. But we were on the wrong beach and I had no idea how to proceed to a map reference rendezvous in the Normandy countryside. To his eternal credit my second-in-command, Pat Macnaghten, knew exactly where we were, and led us to the field which was our destination. Next morning Roy Dunlop and I were enjoying a drink when brother Mike appeared. He was a Gunner Major in 11th Armoured Division (and stayed in the army post war retiring as a Brigadier)

Things seemed cushy – till teatime when the Colonel sent for me to give orders to cross Pegasus Bridge over the Orne and relieve troops holding the village of Escoville on the perimeter of the bridgehead to the east of the Orne captured by airborne troops on D-Day. This bridgehead was considered vital by our high command and the orders to me were quite clear: “You must hold Escoville.”

So our first task in Europe was one unfamiliar to a mobile reconnaissance unit : dig in. This we did, hampered by enemy shell fire, at great speed. The Germans shelled Escoville ceaselessly. They also crept upon us through the high standing corn of lush Normandy farms. For most of us, for me certainly, this was a first experience of close quarter battle and ferocious shelling.

I knew I had above all to maintain the morale of my troops. There were scares in the middle of the night that Germans had infiltrated and of course we had casualties from the shelling. I did have some very fine troop leaders, such as Geoff Clough and Desmond Owen, who had been in the desert fighting as had most of the troop sergeants and senior NCOs. We all held our nerve, some of us taking risks in exposure to danger which in retrospect were a bit foolhardy but which certainly contributed to the performance of the squadron. They say most men give of their best in their first action. Afterwards they know what it is all about, and courage is expendable.

After two days and two nights we were relieved by C Sqn. My squadron retired to a quiet orchard a mile back, alongside Regimental HQ. I got under my vehicle and went to sleep. Within two hours I was woken to be told that the acting CO, Roy Dunlop, wanted a word. I crawled out. “Very sorry, John,” he explained “but C Sqn are in trouble in Escoville. Their Sqn leader went in his armoured car along to the east several hours ago and he has not returned. I want you to go back there for the night and hold the hand of their acting commander.” That I did: and the night was without major trouble. But it was my third night under shellfire, without sleep. For bravery in the Escoville battle I won an MC – and I had myself successfully recommended Clough and Owen for the same award. Three Other Ranks won M.M.s. I felt I had proved myself and gained in confidence to lead my squadron successfully.

The bridgehead battles lasted much longer than we planned. There were all sorts of minor offensive operations, which were unprofitable and often ill-planned. The German Tiger tanks were a menace: 4 CLY for instance lost a whole squadron, killed or prisoner, to three or four bravely manned Tigers in Villers Bocage. 2 DY had landed in France some 700 all ranks strong: by the end of August our casualties were 190 killed, wounded and missing, including 18 officers.

XII BELGIUM, HOLLAND, GERMANY AND WAR’S END

The breakout from the bridgehead came at last in early August, the Germans suffering immense casualties at Falaise, then drawing back over the Seine the bulk of their forces. 2 DY took part in the battle for Le Havre then crossed the Seine near Elbeuf and helped chase the enemy across Belgium into waterlogged Holland. After several months of minor scraps in appalling conditions we reached Maastricht in December.

Then Hitler made his last throw. All the best of German armour was massed for a thrust through the Ardennes on the American front, the aim being to cross the Meuse, get behind the allies and attack Antwerp. On Christmas Day 1944 2 DY was in a British force sent from Maastricht (just as Christmas dinner was ready) via Liege into the Ourthe valley and to the area of Marche to help the Americans. In fact the latter fought bravely and recovered : DY fighting included a highly creditable and much publicised link up with US troops in the South to seal “The Bulge”. The Yanks suffered badly in the extreme cold. They would exchange a Jeep for a bundle of our warm battledress and I did several such deals. I then drew my own name out of the hat to proceed on home leave.

When I returned from leave in a bitter January to Regimental HQ in Marche it was already dark and I elected to stay there overnight in the house they occupied rather than rejoin my squadron in the line and most significantly, to sleep downstairs in the warm rather than in the communal cold bedroom upstairs. That last decision may well have saved my life for during the night the Germans dropped anti-personnel bombs which exploded on the windowsills of the upstairs room where slept all the HQ officers except one on duty by the radio and me. Everyone upstairs was hit, including the adjutant and intelligence officer killed, and three seriously wounded.

Among the wounded in Marche was Roy Dunlop who lost an eye. It was his second wound because he had been with me one early morning in Holland when the two of us were talking with Alec Langly-Smith as a Bosch ‘Moaning Minnie’ mortar bomb came over making its ghastly noise and landed between us. Alec and I fell into the ditch one side and were OK, Roy on the other was hit in the leg and evacuated.

We returned from the Ardennes to Holland, re-equipped and crossed the German frontier to take part in very severe fighting for the Reichswald forest in early February. This was the area of the Siegfried Line. The Germans were defending their native land and did so defiantly. Such place names as Goch and Gennep (where Bill Davies won another MC for B Sqn) will be remembered by all who took part in these desperate battles. We seemed to be in action nearly every day suffering a steady stream of casualties – but we were inexorably making way toward the last great obstacle before entering the heart of Germany – the Rhine.

We reached that great river in March and 2 DY went over, on a floating Bailey Bridge hastily erected under fire by our engineers, with no trouble, on the last day of that month. We streamed on eastward, of course not welcomed as in France (sometimes) or Belgium and Holland (always) but by sullen bewilderment.

We had had a little light relief in Bentheim on the Dutch/German border, where at the station siding an engine was found with steam up and an ex engine driver in our ranks got it moving up and down the line to loud cheers. Then we found a magnificent black Mercedes in a garage carrying a huge swastika on its bonnet so clearly belonging to a high Nazi official. We took that on squadron HQ strength and kept it until war’s end. Then our miserable control commission insisted all such perks must be handed in. Alec Langly-Smith’s brother, a naval officer, had earlier offered to take it home for me via Cuxhaven but I missed the boat!

At ‘O’ (Order) Group meeting on the evening of 3 May the Brigadier in charge gave orders for 4 May. “And, Major Harris, you will have under your command two troops of tanks, for which you have been campaigning to operate alongside your armoured cars since the Bridgehead in Normandy. Their commander is sitting behind you”. I turned : it was Jack Hawkins, with whom I had joined 4 CLY in 1939, almost exactly six years before.

May 4 was a day of triumph. Odd pockets of die hard Germans gave fight but we had our tails up. That evening one of my troop leaders came up on the radio to say that he had a German major carrying a white flag with him – who said his superior officer wished to surrender the 15th Panzer Division, along with the 21st the best armoured divisions in the Wehrmacht, with which allied soldiers from throughout our then Empire had done battle from Alexandria to Tunis, from Normandy to Bremerhaven. I thought, at first, my officer was pulling my leg, but not so. Similar approaches were being made on other fronts. The war in Europe was over.

My C.O. came up to me next day to say how well B Sqn had done. Walter Serocold was of the Reconnaissance Corps of modern creation without the near 200 year old traditions of the Derby Yeo. Modest of stature and retiring of character he had joined us in the Bridgehead taking over a regiment who expected the appointment of one of its own (Roy Dunlop). But Walter was to prove a very able and much respected commander. He had a good brain, was very steady in a crisis and a notably fair man, who never threw his weight about unless justified. He was brave as they come and would be my first choice among the colonels under whom I soldiered.

There followed six months of occupation, stationed near Hamburg. The official policy was one of “non-fraternisation” with the Germans. Whoever conceived that did not know the British soldier! For myself there was little to do. I spent a lot of time organising horse racing at Stade with captured ponies.

Having joined at the beginning of the war I was in an early release group and was demobilised in mid December. For the last two months or so following Walter’s departure I had become second-in-command of 2 Derby Yeo. to Alec Langly-Smith. He and I were both awarded a bar to our MCs for our leadership in the chase through Germany. I had had a ‘good war’ without a scratch.

* * *

My regiment had finished the European war quite close to Belsen and I talked to many of our people who had been there. What they said left me in no doubt that our war was one of the most just in history. The cliché that the Allies saved civilisation just happens to be true. I am proud of my country’s contribution – of course modest compared with America’s men and materials, not to mention the Russians, but let it never be forgotten that but for those airmen in 1940 there would have been no chance to earn those subsequent victories.

That’s enough of the war. I will end by admitting that after a few beers I am quite capable of making jingoistic noises about my small part in it all. But in the cold light of dawn I know it was not small but miniscule. And having just read George Macdonald Fraser’s Quartered Safe Out Here telling the tale of an infantry man’s hand-to-hand epic against Japs on the Irawaddy I know anew how lucky we where to fight the Werrmacht (and never the SS ). GMF’s book ranks in my mind with Cyril Joly’s Take These Men about the Desert War.